A collage of Vladimir Putin placing his hand on Joseph Stalin's shoulder. Richard Cohen's new book Making History details the links between the two Russian leaders. Illustration by Meilan Solly / Photos: Pool / AFP via Getty Images and Fine Art Images / Heritage Images / Getty Images

Author, Making History: The Storytellers Who Shaped the Past

History has ever been a harbor for dishonest writing—a home for forgers, the insane or even “history-killers” who write so dully they neutralize their subjects. Direct witnesses can be entirely unreliable. The travelogue of the 13th-century explorer Marco Polo, which he dictated while in prison in Genoa to a romance writer who was his fellow inmate, is about two-thirds made up—but which two-thirds? Scholars are still debating. Survivors of Josef Mengele’s vile experiments at Auschwitz recall him as tall and blond and fluent in Hungarian. In fact, he did not speak that language and was relatively short and dark-haired. The director of the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial in Israel has said that most of the oral histories collected there were unreliable, however honestly contributed.

Many of these instances can be ascribed to the quirks of human memory. Actual fakery, though, has a long history. As Tacitus begins his Annals, “The histories of Tiberius and Caligula, of Claudius and Nero, were falsified, during their lifetime, out of dread—then, after their deaths, were composed under the influence of still festering hatreds.” In England in the 16th century, it was common to share made-up stories about your ancestors in the hope of achieving greater social standing.

A fascinating, epic exploration of who gets to record the world’s history—from Julius Caesar to William Shakespeare to Ken Burns—and how their biases influence our understanding about the past.

Most countries at one time or another have been guilty of proclaiming false versions of their past. The late 19th-century French historian Ernest Renan is known for his statement that “forgetfulness” is “essential in the creation of a nation”—a positive gloss on Goethe’s blunt aphorism, “Patriotism corrupts history.” But this is why nationalism often views history as a threat. What governments declare to be true is one reality, the judgments of historians quite another. Few recorders set out deliberately to lie; when they do, they can have great impact, if only in certain parts of the world.

“I know it is the fashion to say that most of recorded history is lies anyway,” wrote George Orwell in 1942, reflecting on pro-Franco propaganda in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War. “I am willing to believe that history is for the most part inaccurate and biased, but what is peculiar to our own age is the abandonment of the idea that history could be truthfully written.” The problem continued to trouble him. Three years later, he went further: “Already there are countless people who would think it scandalous to falsify a scientific textbook, but would see nothing wrong in falsifying an historical fact.” Chief among the culprits were the falsifiers of the Soviet Union, in particular Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin.

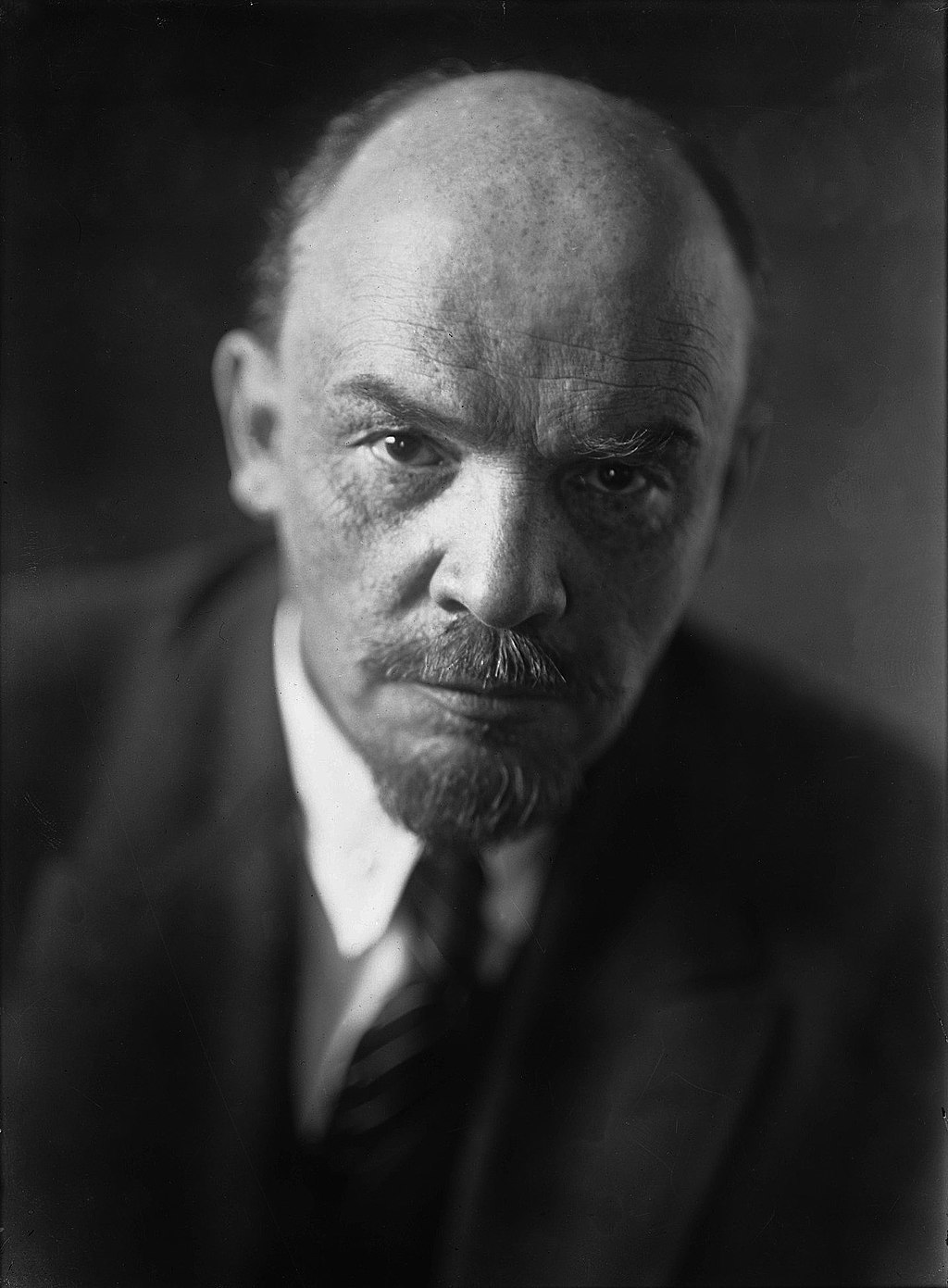

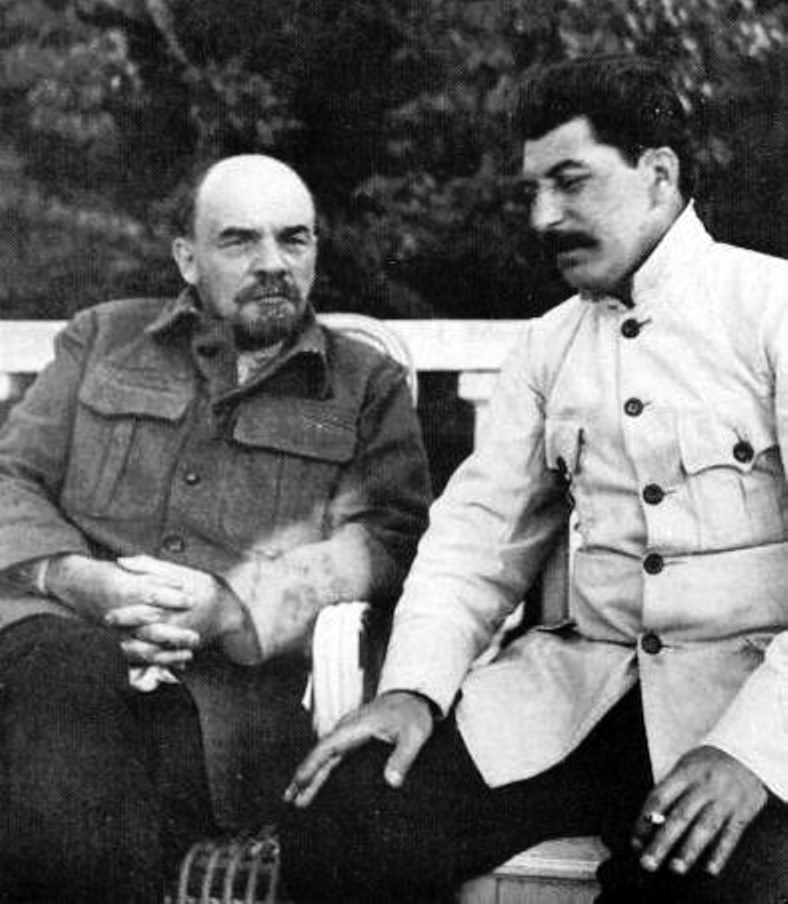

Lenin presided over Soviet Russia from 1917 until his death in 1924, but Stalin (a name he came up with, from the Russian word for “steel”) had usurped much of his authority even before his final illness. As it was, Lenin had already put in place the basic institutions of the Stalinist regime, a state committed to totalitarian rule based on the party, the army and the secret police; the soviets (workers’ councils), in whose name the Bolsheviks had seized power, had long been rendered impotent. Starting with the Red Terror of 1918, Lenin and Stalin shared responsibility—by enforced famine, brutal imprisonment, mass killing, ethnic cleansing or assassination—for the deaths of some 20 million. In one of the peak periods of Stalin’s regime, from 1937 to 1938, seven million were arrested (Communist Party leaders were given quotas of “enemies” to be turned in), with a million executed and two million dying in concentration camps. At the height of this violence, 1,500 people were being shot every day. “Ten million,” Stalin told British Prime Minister Winston Churchill as his tally for the dead, holding up both palms in the Kremlin in 1942. But that figure has been reckoned low, given the vast numbers who perished in what has come to be called the Holodomor (“hunger-death” in Ukrainian). (Coincidentally, Lenin and Stalin shared the same cook—the grandfather of current Russian President Vladimir Putin, who has promoted a distinctly ahistorical version of 20th-century history amid his ongoing invasion of Ukraine.)

In her history of Eastern Europe, Anne Applebaum writes of the “peculiarly powerful combination of emotions—fear, shame, anger, silence—[that] helped lay the psychological groundwork for the imposition of a new regime,” Stalin’s Soviet Union. The completeness of the state, the pervasiveness of every institution from kindergarten schools to the secret police, put an end to independent historical inquiry. In this brave new world (Orwell described Soviet commissars as “half gramophones, half gangsters”), historians were not just to do Stalin’s bidding; if, in his eyes, they failed to do so, their lives were ruined and often shortened. For instance, Boris Grekov, director of Moscow’s Russian History Institute, had seen his son sentenced to penal servitude and, in terror, made wide-ranging concessions to the Stalinist line, writing books and papers to order.

Another leading historian, Yevgeny Tarle, was one of a group of prominent historians falsely accused of hatching a plot to overthrow the government; he was arrested and sent into exile. Around the same time, between 1934 and 1936, the Politburo, or policy-making body, of the Russian Communist Party focused on national history textbooks, and Stalin set scholars to writing a new standard history. The state became the nation’s only publisher. Orwell had it right in Nineteen Eighty-Four, where the Records Department is charged with rewriting the past to fit whomever Oceania is currently fighting. The ruling party of Big Brother “could thrust its hand into the past and say of this or that event, it never happened—that, surely, was more terrifying than mere torture and death.”

Stalin, too, wrote his own version of events, contributing part of a “short course” on the history of the Soviet Communist Party. In his teens, vozhd (the boss), as he liked to be called, had been a budding poet, and now he contributed verse for the national anthem, improved on several poets’ translations and even made changes to the film script of Sergei Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible. He was a master of what could be done with language; under him, the euphemism “extraordinary events” was used to cover any behavior he considered treasonable, a phrase that covered incompetence, cowardice, “anti-Soviet agitation,” even drunkenness. The great Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert was to refer to Stalin ironically as “the Great Linguist” for his corruption of language.

“Uncle Joe” himself died peacefully, aged 74, on March 5, 1953, after three decades of bloody rule. Three years later, his successor, Nikita Khrushchev, announced a special session in which he gave delegates a four-hour “secret speech” denouncing the former leader and providing a radically revisionist account of Soviet history that included a call for a new spirit in historical work. Practitioners were admonished to upgrade their methods; to use documents and data to explain rather than simply proclaim past Bolshevik views; and to write a credible account—one that would include setbacks, confusions and real struggles along with glorious achievements.

So began a “thaw” that saw Stalin repudiated throughout the Soviet Union, political prisoners released and prison camps dismantled, ushering in a season of “free thinking” that, for instance, saw the publication of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and Not by Bread Alone, Vladimir Dudintsev’s bestselling 1956 novel about a physics teacher who invents a labor-saving machine that is rejected by bureaucrats because the innovation runs up against Soviet dogma. Khrushchev even set up a commission to protect defamers of Stalin. One high school history teacher staged a mock trial of Stalin in his class, while activists in Moscow put on an evening of poetry and music performed by and in honor of gulag survivors. By early 1955, lively discussions centered on the journal Voprosy istorii (Problems of History).

“You still had to toe a Marxist line,” says Dominic Lieven, an expert on Russian history at the London School of Economics, “but by the 1970s in many cases you could get away with quoting Lenin in the introduction and then providing much valuable info and ideas in the text.” Academics were allowed room for maneuver, so long as it was exercised discreetly and deniably, but they were not free of political controls regarding what material they saw, their links with historians overseas and what they could write. They had to observe a code of conduct—poniatiia, literally “concepts.”

For other members of the Politburo, the thaw, such as it was, seemed too much. In October 1964, Khrushchev was toppled, and Leonid Brezhnev took his place. Many innovations were reversed. Other conservative leaders followed—Kosygin, Andropov, Chernenko. In 1968, during Czechoslovakia’s Prague Spring, this same process of opening up for a bit, then closing down again, repeated itself. Prisoners from the Stalinist period were released, some writers were rehabilitated and recent events were reexamined with more openness. Then the tanks came.

As became typical for Soviet historians, in March 1974, P. V. Volobuev, director of the Institute of History and a leading figure in new history-writing, was fired; a book of essays suggesting that Russia was a backward country in 1917 was condemned. It was not until March 1985, when Mikhail Gorbachev took charge, that the writing of history was given a measure of freedom from government control. As David Remnick relates in Lenin’s Tomb, his prize-winning look at the Soviet Union morphing into modern Russia:

Something had changed—changed radically. After some initial hesitation at the beginning of his time in power, Gorbachev had decreed that the time had come to fill in the “blank spots” of history. There could be no more “rose-colored glasses,” he said. . The return of historical memory would be his most important decision, one that preceded all others, for without a full and ruthless assessment of the past—an admission of murder, repression and bankruptcy—real change, much less democratic revolution, was impossible. The return of history to personal, intellectual and political life was the start of the great reform of the 20th century.

Boris Yeltsin, who served as first president of what was called the Russian Federation from 1991 to 1999, allowed yet further freedoms. The old textbooks became so completely devalued that history examinations had to be postponed throughout the Soviet Union. (In Estonia and Ukraine, laws were introduced that made writing bad history a prosecutable offense.) By 1989, Remnick notes, books had appeared in Russian schools with chapters on the Soviet period that resembled dissident writer Solzhenitsyn more than the approved texts of earlier generations.

Historians who had previously been obedient communists felt emboldened to come out in their true colors. Particularly notable was Dmitri Volkogonov, whose father had been arrested and shot in Stalin’s purges and whose mother had died in a labor camp during the Second World War. In 1945, the orphaned Volkoganov, aged 17, joined the army, and over some four decades rose to the rank of colonel general and the positions of special adviser for defense to Yeltsin and head of the Soviet military’s psychological warfare department. More than this, he was a talented historian, and in 1988, after years of research in secret archives, published an outspoken biography of Stalin that acknowledged his subject’s strengths but also frequently contradicted official versions of events and argued persuasively that it was only under Stalin that the Soviet Union became the “dictatorship of one man.”

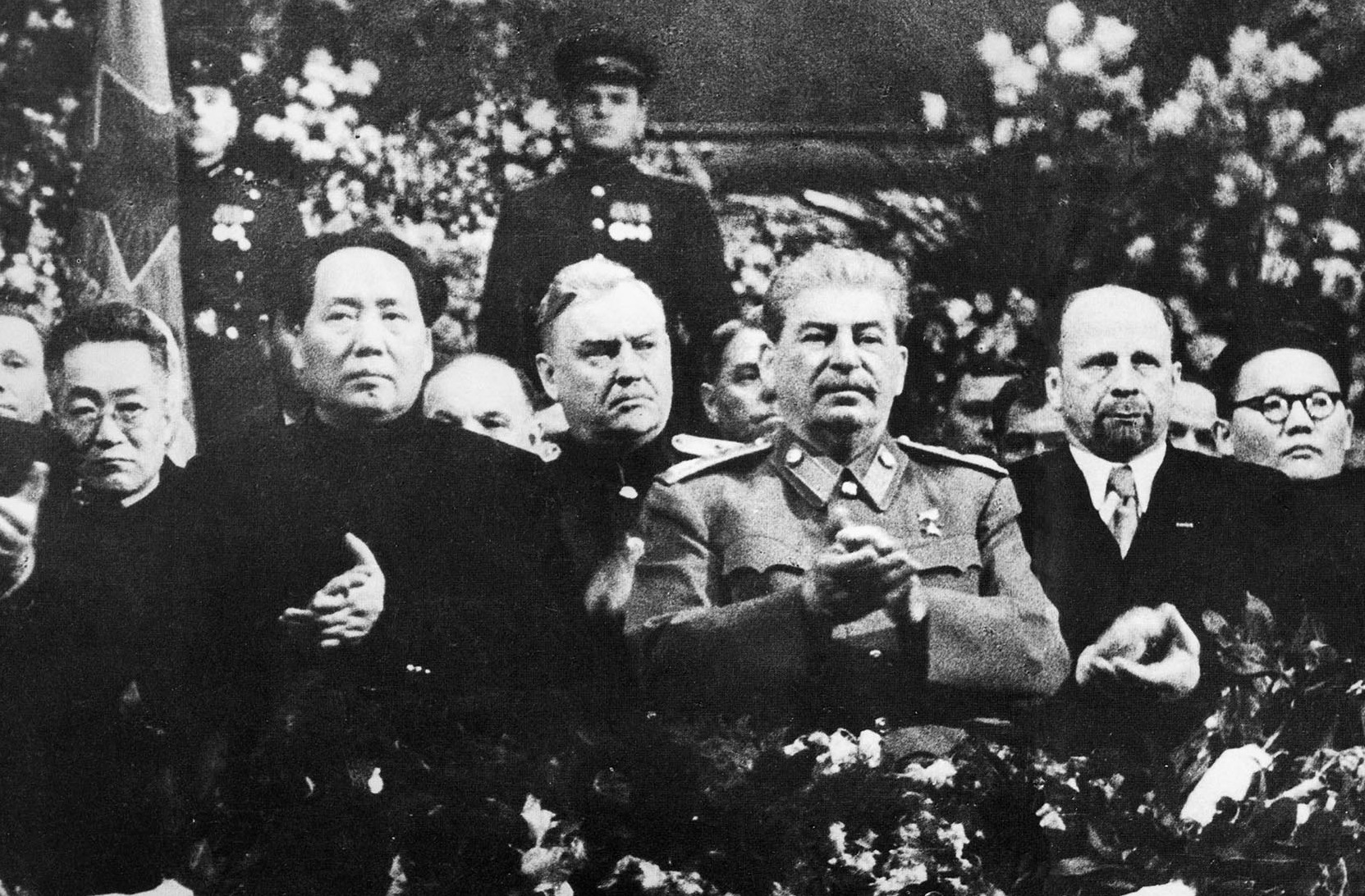

By 2015, Yeltsin’s laissez-faire policies had long been revised by the controlling hand of Vladimir Putin, who took over as prime minister in August 1999 and is now in his fourth term as the country’s president. His views of his country’s recent history were clear. The Soviet Union was the last, not the first, European country to sign a deal with Nazi Germany: Western deals with Hitler were the real disgrace. In September 1939, the Soviet Union did not attack Poland; it merely protected territory abandoned by the collapsed Polish state. And so the defense of Stalin’s diplomacy has continued.

From the start, Putin appreciated the effectiveness of historical rhetoric for his nationalist agenda, particularly if it played to popular nostalgia for the Soviet Union, the collapse of which was a humiliation for most Russians. This was a point emphasized by historian Orlando Figes in a 2009 article on Putin’s approach to controlling the historical record as far as Russians are concerned. As he summarized their situation: “In a matter of a few months they lost everything—an empire, an ideology, an economic system that had given them security, superpower status, national pride and an identity forged from Soviet history.”

Polls in the year that Putin came to power showed that three-quarters of his people regretted the breakup of the U.S.S.R. and wanted Russia to win back lost territories such as Crimea and eastern Ukraine. As Figes argues, they were resentful about being told they should be ashamed of their history. They had been raised on the Soviet myths: the great liberation of the October Revolution, the first five-year plan, the collectivization of agriculture, the defeat of the Trotskyites, Soviet achievements in culture, science and technology. Why should they feel guilty? Today, even Soviet-era secret police uniforms are on sale. Putin promptly created his own version of history, combining Soviet myths (sans their communist baggage) with stories from the Russian Empire before 1917, and when the centenary of the revolution came, his government studiously ignored it.

Putin has not denied Stalin’s crimes (on the contrary, on several occasions he has publicly acknowledged them), but he urges that they should be set against Uncle Joe’s achievements, above all victory in the Great Patriotic War of 1941 to 1945. It makes for an odd balancing act. In 2015, a gulag museum opened in Moscow—but most labor camps and mass graves have not been commemorated and are gradually being destroyed or removed. As the Russian emigré Masha Gessen has written, “[E]very museum, indeed every country, ultimately aims to tell a story about the goodness of its people.” But Gessen can still talk of a “mafia state ruling over a totalitarian society” without it seeming a gross overstatement.

The first use of actual violence in the service of Putin’s control of history came on December 4, 2008, when masked men from the Russian General Prosecutor’s Office forced their way into the St. Petersburg offices of Memorial, a civil rights group that since 1987 has pioneered research into Stalinist repressions. The men confiscated 12 hard drives containing information on more than 50,000 victims of repression and other documents dated to between 1917 and the 1960s. In September of the following year, Mikhail Suprun, a Russian historian researching German prisoners of war sent to Arctic gulags, was arrested. His apartment was searched, and his entire personal archive was confiscated. He was told he faced up to four years in jail. Russia’s FSB intelligence agency also arrested a police official who had handed over archive material to the historian. A human rights campaigner in the Arkhangelsk region where the gulag was situated commented, “What we are seeing is the rebirth of control over history. The majority of Russians don’t have any idea of the scale of Stalin’s repression.” Later, in January 2018, the Culture Ministry withdrew the distribution license for The Death of Stalin, Armando Iannucci’s black comedy about the Soviet leader and his immediate circle.

In late 2011, a leading member of Memorial said that today’s power is very rational—it doesn’t shut everyone up. “There is freedom of expression and speech,” Arseny Roginsky told the New Yorker. “There are shelves of anti-Putin books in the stores.” But that optimistic view was uttered 11 years ago. Since then, Putin, who doesn’t care if his critics think he is “on the wrong side of history,” has become ever more intent on a single narrative, controlled by the Kremlin, about what Russia was, which means he will continue to deny the full complexity of its history, molding a collective memory through propaganda, the media and officially sanctioned books.

In an essay first published in 1990, the historian Eric Foner concluded:

Sometimes . history serves mainly to rationalize the status quo. History can degenerate into nostalgia from an imaginary golden age, or inspire a utopian quest to erase the past altogether. And it can force people to think differently about their society by bringing to light unpleasant truths. In today’s Soviet Union, it is playing all these roles and more.

Whatever the intentions of Putin’s campaign, the current regime’s attempt to alter the historical record is hardly realistic. The opening of the archives, the publication of their documents and the work of organizations like Memorial have made that infeasible. Even so, as long as the government promotes self-serving patriotic myths, bad history will continue to be written and propagated.

Copyright © 2022 by Narrative Tension, Inc.. From the forthcoming book Making History: The Storytellers Who Shaped the Past by Richard Cohen to be published by Simon & Schuster, Inc. Printed by permission.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

Richard Cohen is the author of By the Sword, Chasing the Sun, and How to Write Like Tolstoy. The former publishing director of two leading London publishing houses, he has edited books that have won the Pulitzer, Booker, and Whitbread/Costa prizes, while twenty-one have been #1 bestsellers. He has written for most UK quality newspapers as well as for The New York Times Book Review and The Wall Street Journal, and is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. His new book, Making History, is due out from Simon & Schuster on April 19, 2022.